- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

Peter Zenger's Trial

29 September 2011

Many revolutionaries and forward thinkers are well known; Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Friedrich Nietzschie, Che Guevara, Karl Marx. There's one you may never have heard of: Peter Zenger. And yet, without him, the rest of those people may have been just mere blips in the pool of obsolete history. What Peter Zenger accomplished set the stage for others, and yet he is obscure to most Americans.

Peter Who?

John Peter Zenger was a typical immigrant living the “American Dream” before there even was an America to live it in. He was born 26 October 1697 in the Palatinate region of what is now Germany. In 1710, he immigrated to the British American Colonies with his family. Some say his father died en route, and as a result, his impoverished mother had to “sell” him to a printer as an indentured servant. Whether that bit of the story is true, we do know that Peter Zenger was apprenticed from 1711 to 1719 to a printer by the name of William Bradford of New York, who published The New York Gazette. Here he learned the trade, and after having a failed partnership with his mentor, he set out on his own.

In 1726, Peter Zenger began to make a name for himself as a printer in his own right, printing things like religious tracts and the occasional advertisement. By this time, he had been married to a woman by the the name of Anna for about four years and had several children. Anna was his second wife, as he was a widower at the time of the marriage in 1722.

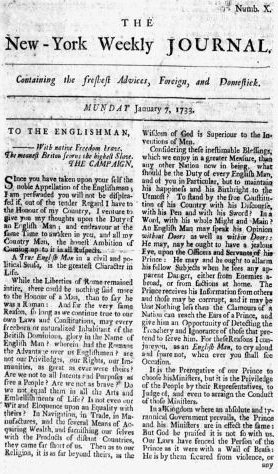

Peter Zenger is known best for a newspaper he edited and published, a newspaper which rivaled that of his mentor. That paper was known as The New-York Weekly Journal. There is some confusion as to the founder of the newspaper, however. Some sources say Lewis Morris, a former judge, was the founder, whereas others say either prominent New York attorney James Alexander or Zenger himself was the founding father of The New-York Weekly Journal. Regardless of who founded it, Zenger was the publisher, and his name was cited on the front page. In 1733, the newspaper printed its first edition and soon gained the ire of the Royal Governor of the Colony of New York, Sir William Cosby.

Not to be confused with that comedian of the same name

Cosby was controversial, even by today's standards. Born in Ireland, he rose to prominence in Great Britain by way of the British military. In 1732 he came to New York to take over as Royal Governor. Very soon after he arrived, he was embroiled in one legal scandal after another. He often circumvented the legal system to get what he wanted. He became involved in a salary dispute with the former acting governor and as a result removed the colony's Chief Justice Lewis Morris as judge when Morris did not go along with Cosby's wishes on the resolving verdict. He set up a puppet, Francis Harison, as editor of William Bradford's Gazette, and set about adopting arbitrary measures in governing his colony.

It was in reaction to these controversies that The New-York Weekly Journal was founded. The paper was supported by a local political power opposed to the governor and his lackeys. From the first edition onward, critiques and editorials regarding the actions of the leadership of the Colony of New York were printed. Thinly veiled attacks of the governor and his actions were commonplace and often times the front page of the journal offered arguments as to why people should be critical of their leaders. Soon Zenger found himself in hot water for what he published.

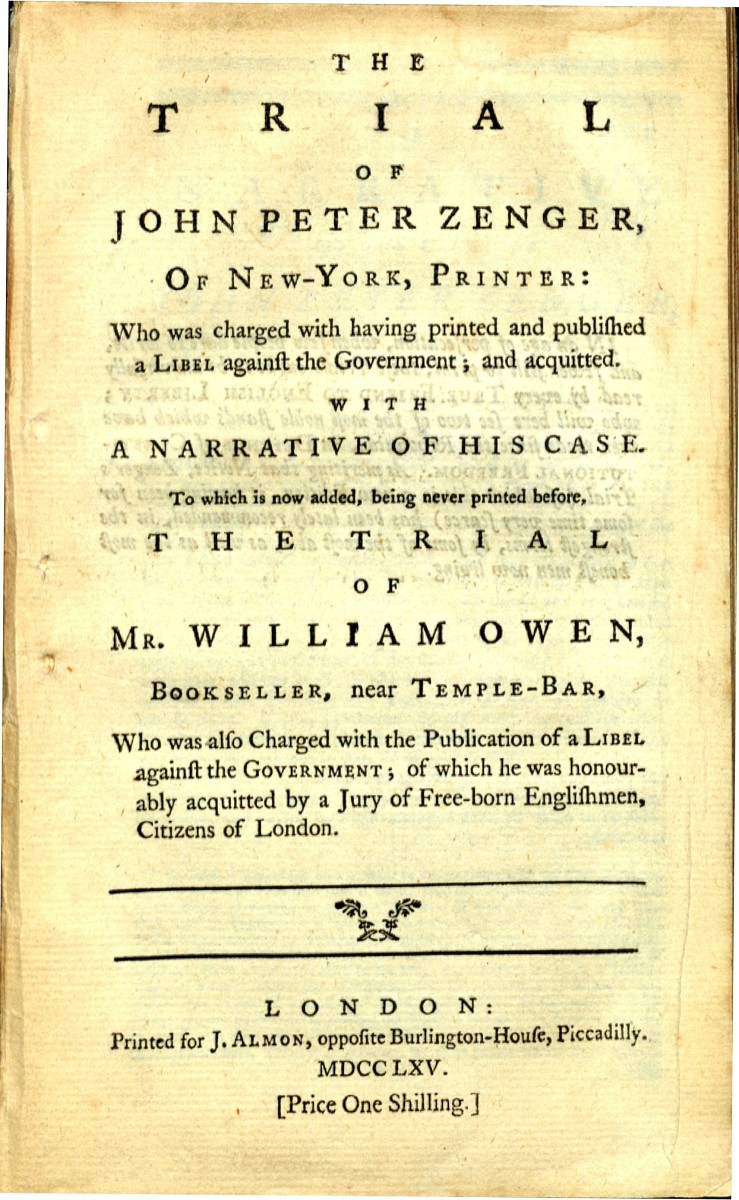

Cosby was livid when he read of the perceived incursions against his character in The New-York Weekly Journal, even though most of what as printed was true. He set about to destroy the paper. First he tried to have copies publicly burned and the press shut down, and when that did not succeed, Cosby ordered Peter Zenger thrown into jail and indicted with seditious libel in 1734. Even though Zenger was not the author of most of the articles that criticized the official actions of the leadership, he was the one charged because he was the publisher, and therefore editor, of the paper at the time. Sources say that James Alexander or Lewis Morris or their supporters were the authors of the mostly anonymous articles.

For 10 months, Zenger awaited trial in prison, partly because he could not pay the fine of 800 pounds, then an astronomical amount of money. Refused a lawyer to consult with, Zenger continued to publish his paper, giving directions to his wife and friends from a hole in his cell door. As a result, it is said that only one issue of the paper was missed the entire time the publisher was imprisoned.

It would take a Philadelphia lawyer to get him off

After Cosby managed to have both James Alexander and fellow attorney William Smith disbarred for trying to defend Zenger, Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton decided to take on Zenger's case pro bono. There is some suggestion that Benjamin Franklin swayed Hamilton, as the two were presumably friends. Hamilton was about 60 years old, of Scottish origin, and was a prominent and influential figure in the circles of Colonial America at the time.

At the trial in August of 1735, Hamilton argued that Zenger's published articles were neither seditious nor libelous because they were based of true facts. At the time, English law stated that any injurious statement or criticism that fostered any ill opinion of any governmental official whether true or not was libel, thus making Hamilton's defense of Zenger invalid. However, the Philadelphian lawyer was determined to make his case. Several times Hamilton was objected by the judges presiding, notably Justice James Delancey, a Cosby ally. Though the defense was excluded by technical legal grounds, Hamilton was able to sway the jury and convinced them to find Zenger not guilty.

Incidentally, this is also where the saying “It would take a Philadelphia lawyer to get him off” would come from, though its use would not be for several more years.

We need a hero

The case was instantly hailed as a success by the colonies and both Zenger and Hamilton were hailed as heroes, with their fame extending even to England. The verdict was hailed as a milestone in asserting Colonial freedoms and the establishment of truth as a defense against the charge of libel.

No longer did American Colonial newspapers have to worry about charges of sedition or libel being brought against them for printing the truth As a result, many other newspapers and printers sprung up, heralding in an era of print.

The verdict also allowed for correspondence to flow freely between the colonies, creating sort of an informal colonial association that pooled information, exchanged ideas and soon coordinated protests against the British government. This would continue for the next forty years until the American Revolution.

What happened to the key players?

William Cosby died of tuberculosis only a year after the verdict. He was Governor of New York up until his death, ever remaining a symbol of the oppression of royal governors.

Andrew Hamilton became a trustee of the general loan-office of Pennsylvania and a judge of a vice-admiralty court. He died in Philadelphia in 1741.

John Peter Zenger would become the public printer for the colony of New York in 1737 and for the colony of New Jersey in 1738. Presumably he continued his printing businesses until his death in 1746.

So what does this mean to me?

The idea that there is a fundamental right to freedom of speech and freedom of press would become the basis for part of the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. This idea, radical at the time, has become a law of the land and the basis that has become the rallying cry for every revolutionary since.

As Gouverneur Morris, the penman of the United States Constitution, wrote, “The trial of Zenger in 1735 was the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America.” (Sourced by both Wikipedia and Russell Freedman)

Recommended reads:

Works Referenced

Carruth, Gorten. The Encyclopedia of American Facts and Dates. 10th Ed. Harper Collins: New York, 1997. 56

Davis, Kenneth C. Don't Know Much About History: Everything You Need to Know About American History But Never Learned. Perennial: New York, 2003. 58-59

Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor N. Dupuy. An Outline of the American Revolution. Harper and Row: New York, 1975. 11

Freedman, Russell. In Defense of Liberty: The Story of America's Bill of Rights. Holiday House: New York, 2003. 46-48

Goldman, Steve. “The Acquittal of John Peter Zenger: The First, First Report.” HistoryBuff.com – A Non-Profit Organization. R. J. Brown and the Newspaper Collectors Society of America, 2009. 28 September 2011 From http://www.historybuff.com/library/refzenger.html

“John Peter Zenger”. Encyclopedia of American History. Richard B. Morris. Harper Row: New York, 1970. 808

Linder, Doug. “The Trial of John Peter Zenger: An Account” Seminar in Famous Trials. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. 2001. 28 September 2011 From http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/zenger/zengeraccount.html

“Marriage Record of Johan Peter Zenger and Anna Catha Malin” . The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record (quarterly), 1882, selected extracts . New York Genealogical and Biographical Society: New York. 77. Found in New York City Marriages, 1600s-1800s [database on-line].Genealogical Research Library, comp. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005.

Moran, Michael, John Lesniak, Cynthia McCormick, and Kelli Flansburg, “The Crown v Zenger : The Trial of John Peter Zenger”. Cases. The Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York. 28 September 2011 from http://www.courts.state.ny.us/history/zenger.htm

Tindall, George Brown and David Emory Shi. America: A Narrative History. Volume 1. 5th Ed. W. W. Norton and Company: New York, 2000. 95

Shafritz, Jay M. The Harper Collins Dictionary of American Government and Politics. Harper Perennial: New York, 1992. 61, 427

Wikipedia contributors. "Andrew Hamilton (lawyer)." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 23 Sep. 2011. 28 September 2011 from //en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Andrew_Hamilton_(lawyer)&oldid=451991091

Wikipedia contributors. "John Peter Zenger." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 21 Sep. 2011. 28 September 2011 from //en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=John_Peter_Zenger&oldid=451722606

Wikipedia contributors. "William Cosby." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 22 Sep. 2011. 29 September 2011 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Cosby

Woodward, W. E. A New American History. Garden City Publishing: New York, 1936. 100-101